Those who were hopeful that “Liberation Day” would provide clarity and reduce uncertainty – and with it, reduced market volatility – were disappointed. They did get details, but not clarity. And the details were not pretty. Uncertainty continues. The probability of a recession has increased.

The proposed tariffs are draconian. A floor 10% tariff on all imports coupled with “stacked” penalty tariffs on top of reciprocal tariffs. The breakdown has been detailed in several publications and won’t be repeated here. At some level, the announced tariffs are a negotiation strategy. The objective is to get other countries to reduce their tariffs on U.S. imports. Some countries responded expressing an interest in negotiating. Others have announced retaliatory tariffs, most notably China which started at 34%. In the hours that followed, the U.S. and China have raised tariffs even higher in a high stakes game of chicken. China has devalued its currency to offset some of the impact of tariffs on the cost of its exports. The effect is higher costs for its citizens. Its retaliation has also included the sale of U.S. bonds which has swiftly increased yields, thereby increasing the cost of borrowing.

The President made a social media post yesterday saying that 75 countries have asked to negotiate without retaliatory tariffs at this time. As a result, he postponed many of the planned tariffs for 90 days. The markets responded with an extraordinary rally.

The new tariffs, coupled with existing ones, could bring U.S. tariffs up to 23%, the highest since the early 1900’s which had terrible consequences (refer to the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930). Tariffs at that level will dampen short-term economic growth which has already been slowing. Estimates are that the announced tariffs represent a 1% drag on GDP for 2025 and a 1.5% to 2% increase in core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE), the Fed’s preferred inflation measure.

But the inflation may not be systemic. As an investment strategist for Natixis Investment Manager Solutions put it: “Inflation will rise, if these tariffs are implemented, but there is a big difference between a price level-shock and a persistent inflationary process.”

In a recent blog, I opined that an overbought market and China’s DeepSeek AI announcement were the impetus for the market drop that had occurred prior to last week. The tariff announcement was the catalyst for the final push down to fair value levels. Ignoring yesterday’s rally, the equity markets have tumbled into correction territory (bear market territory for the Nasdaq).

What has become even more clear, is that President Trump is firmly entrenched in his position that tariffs are good for the economy in the long run and a meaningful source of potentially debt-reducing income. Getting other countries to the negotiating table is one thing, but to no good end if he is not willing to make concessions. He has been arguing for increased tariffs since the 1980s. Further, he now says he wants to eliminate trade deficits. In fact, a part of the formula used to determine the proposed tariff rates is the size of the trade deficit with each country. The point being that tariffs at some levels are here to stay.

It could be months before we know what the final tariff structure will look like. It depends on how long the negotiating process will take. If the President can effectively get his “level playing field” result of equal, but fair, reciprocal tariffs, it may dampen market volatility. If higher-for-longer tariffs meet higher-for-longer inflation, volatility will continue.

Businesses may bear some of the burden caused by the tariffs with slowing revenues or margin compression. As we pointed out in the blog noted earlier, margins are high so businesses may elect to absorb some margin compression rather than passing price increases through to buyers. Consumers can’t absorb higher prices with falling nominal income and unemployment creeping up, so demand destruction is a likely outcome. Bottom line: recessionary forces are building. Quite a shift from where we were just a few weeks ago. Will the Fed come to the rescue? The bond market says yes, predicting four to five rate cuts this year. Fed Chairman Powell says not likely. A recession is not the base case scenario, but the likelihood has certainly increased.

I took a break from this writing to attend a luncheon meeting sponsored by First Trust at a nearby hotel. First Trust’s award-winning (for his accuracy) Chief Economist, Brian Wesbury was a speaker. Brian’s long-standing position is that the growth of the money supply caused by artificially low (zero) interest rates and quantitative easing (printing money), rapid and excessive government growth and spending have choked economic growth. In 18 years, we have tripled the money supply going from $7 trillion to $21 trillion! We created an artificial economy with zero interest rates for 9 years. Non-defense government spending makes up 20.4% of GDP. Every one of these dollars is shifted away from the productive part of our economy. He believes that those spending excesses and free money come at a price we haven’t paid yet. The price could take the form of recession or perhaps the short-term dislocation caused by the imposition of tariffs on other countries. (More on that below.)

In his discussion, Wesbury talked about the need for a productive growth economy, recognizing that personal wealth creation for the rich and poor and those in between, comes from a growing economy. In the post-World War II years from 1949 to 1965 the real GDP growth rate was 4.3%. The great “middle class” was created. From 1966 to 1982, the Great Society and Nixon years, the GDP real growth rate slowed to 2.7%. From 1983 to 2000, the Reagan and Clinton (he of two balanced budgets) years, the growth rate grew to 3.8%. From 2001 to 2024, the GDP has fallen to 2.1%. At a 2% growth rate, it takes 36 years to double the size of the economy. At a 4% growth rate it takes just 18 years. A growth rate of 2% will not increase the financial wellbeing of anyone. There is a need to boost economic growth, and industrial production is a necessary engine.

Wesbury pointed out that, since 2007, real (without inflation) PCEs on goods have grown by 62%. Industrial production has fallen by 8%. The GDP growth rate has been a meager 2% as a result. That is not conducive to a growth economy. How did we get here? Since the 1960’s we have operated on the Keynesian theory that consumption drives economic growth, not productivity. We have encouraged spending and big government with extraordinary stimulus payments beginning with the “Great Society” years and exacerbated by the excesses of the Covid years. At the same time, we discouraged savings. We tax the rich who have a high propensity to save and transfer the money to people who have a high propensity to spend. The personal savings rate as a percent of after-tax income has fallen from 12% in 1965 to less than 4% today. Thirty-five percent of Americans have nothing in savings. Savings create the capital to fuel economic growth through investment and innovation.

What does this aside have to do with tariffs? Wesbury, like most economists, dislikes tariffs. To him, they’re a tax. Wesbury’s preferred solution to our economic problems is smaller government and less fiscal stimulus (spending). In his view, we overtax and overregulate the productive side of the economy. But he does not see that changing anytime soon. So, while he views tariffs as a flawed solution, he sees them as the only tools left in the toolbox to stimulate long-term growth. He finds himself supportive of a rational (will we get one?) tariff policy, the obvious and acknowledged short-term problems notwithstanding. A voice in the wilderness to be sure, but I found it interesting to hear his perspective.

Historically, there are many examples of long-standing high protective tariffs not serving countries, including the U.S., well. But how has China rapidly become a manufacturing powerhouse and the second largest economy in the world? In part because of tariffs. China has had 40% to 50% tariffs on most American imports for years. It encouraged the consumption of local products by creating high prices on imported goods and grew exports to boost their economy. The standard of living has improved in China because of its high economic growth rate over many years. India has followed the same strategy and has seen rapid industrial growth and a higher standard of living as well. While both countries have used tariffs to grow their exports, low labor costs, and in China’s case subsidies to support their companies, have also fueled their growth. The EU and Britian have used a Value-Added Tax (VAT) as well as tariffs to discourage the import of U.S. products.

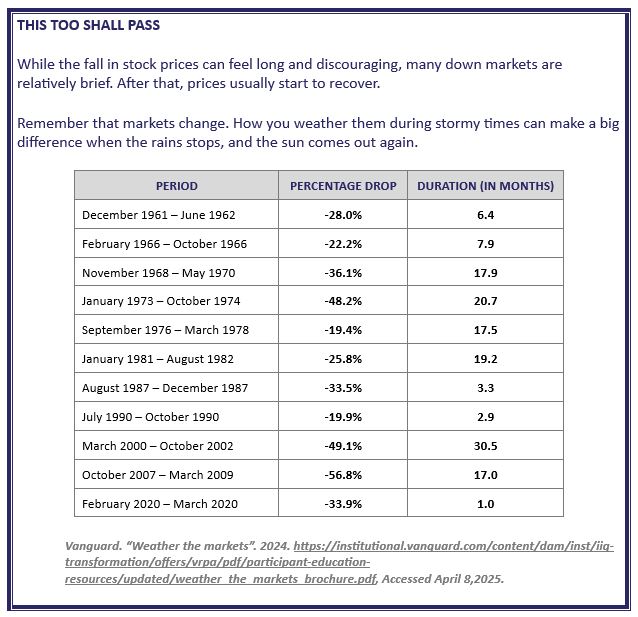

The markets will recover, and that may have begun yesterday. It’s too early to tell with the market bouncing in every direction with the hourly news. Please see the table below for a look at historic recovery times for corrections like this one.

#EconomicImpact #Tariffs #TradeWars #MarketVolatility #GlobalEconomy