“What do you think my company is worth?” As a firm that provides both business appraisal and M&A advisory services that is the twenty-four thousand dollar question that we get asked all the time. And why not? It’s pretty important in any context.

But this is not as straightforward of a question as one might think. What adds to the complexity of the answer is when you wade into the world of privately held middle market companies. Unlike the public markets, where companies are priced ‘efficiently’ all throughout the day by informed investors with access to financials and a whole host of other disclosures, private companies are more of a black box. There is no ready, liquid market and they are priced at a point in time, not continuously. They also have different corporate structures, more limited access to capital, relatively heightened risk profiles (when compared to their public brethren) and different ownership dynamics. All these factors, amongst others, lead us to an ambiguous answer to the question posed: a private company can have multiple correct values at any point in time.

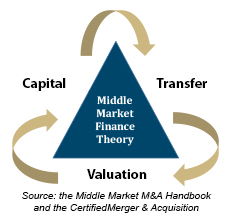

Do I have you confused? Well, hopefully only temporarily. For the purpose of this piece, I am going to ignore all of the nuance in the formal appraisal world and rather just focus on valuation through a private capital market lens (how investment and financing decisions are made vis-à-vis private middle market companies). I am also generally speaking to companies that are above (larger) the mom and pop main street businesses (which are a large and vital component of our economy in their own right), and below (smaller) than public companies and other private monoliths. What are the elements that would lead a company to have multiple correct values? It can be distilled down to capital, transfer channel and value relativity. Let’s explore.

Capital:

The common line is “capital is king.” That’s true, but at the risk of stating the obvious, not all capital is equal nor does all capital ask for the same things. First and foremost, capital providers have changing appetites, and, as such, a cheaper form of capital that could be employed to grow or acquire a business might not be available (where it once was a month or quarter ago).

A good example would be a local bank that was at one point looking for lending opportunities in the hotel industry. If now they have developed too much of a concentration, or if credit quality across the industry is starting to become a concern, that same local bank might shut off that proverbial “spigot” and now lower cost senior debt is no longer available. Same dynamic can be said for private equity relative to their current investment mandates or needs of their portfolio companies. Capital providers carry with them different return requirements. Banks might be happy to take a return of 5% to 6% where private equity is up towards 30%. All else being equal, the higher the cost of a provider’s capital, the lower the value. The point here is that value is impacted by what capital is available to a company and the associated cost.

Transfer channel:

Transfer channels, or exit channels/buyer types to put it in other ways, have a direct implication to value. Transferring a business to a family member or management team would result in a different value than if an owner desired a sale to a strategic or private equity buyer. There are many reasons for exit channel value differences; the ability or lack thereof to generate revenue and expense saving synergies being some of the most common. In the lower middle market, it is often motives and desires of the principal owner(s) that shape the transfer channel decision. Preserving a family legacy or ensuring a community presence may lead to one route whereas pursuing the goal of maximizing the purchase price could lead to another path.

As it seems to be with everything these days, the channels are not as straightforward as they used to be. Yes, there are strategic buyers, financial buyers and related buyers (e.g., management, partners, family), but there are now many flavors of private equity. There are not only platform buyers, but hybrid add-on buyers and PE-financed management buyout investors as well. We have not even gotten to the emerging presences of family offices and independent sponsors. Notwithstanding the increasingly large private equity menu, the broader point here is that an owner’s exit goals can guide them away from one channel and toward another that has meaningfully different requirements and levers to pull. As a result, the selection or decision to prioritize one transfer channel over another can lead to different valuation outcomes.

Value relativity:

One would think two like companies selling similar products in the same space with comparable revenue and profitability would be worth roughly the same amount. True on the surface, but the value equality would quickly evaporate if only one company had a much deeper management team, a better product development program, state of the art equipment, well-documented financials and so on and so forth. A better run company being worth more is intuitive, but why? A lot of reasons, but at the heart of it, it’s because a buyer has more confidence that they will be able to realize the cash flow from said company.

Expanding on this dynamic, one way value can be summarized is the present value of a benefit stream (e.g. cash flow). Coming to a present value requires there be an assessment of risk and well run, diversified businesses are viewed to have less risk naturally. Moreover, every transfer channel, or buyer, has a different ability to fully capture (or not) said benefit stream depending on whether they are a competitor, vendor, consolidator, or any other type of buyer to whom we have alluded. In the same vein, the transfer channels also have dissimilar return requirements and interpret the risk associated with achieving those returns differently. In the end, variability of realizing a benefit stream and different risk/return profiles leads to an array of value opinions.

In the world of formal valuation, there is a cornucopia of value definitions (standards of value) that causes an appraiser to apply certain approaches and methods as well as employ different assumptions. It is important to note that the basis for a formal valuation can lead to different value conclusions for the same company. Returning to our private capital market angle and the question of “what is my company worth?”, the value of a company can again have significant variability depending on its capitalization (or how it is financed or how it can be levered and the associated expense), the transfer channel that facilitates an owner’s exit, and the assessment of realizable cash flow adjusted for growth and risk. When posing this all important question in the context of a private company seeking a new investor or owner, it is important to factor in these elements and to understand their impact when developing your goals and expectations.

Peter Clarke

Chief Operating Officer

BaldwinClarke

Email: peterclarke@baldwinclarke.com

About the author:

Peter is the Chief Operating Officer of BaldwinClarke and a Senior Associate with BaldwinClarke’s investment banking practice. Peter spent over 10 years as a financial analyst in the private equity industry space before joining BaldwinClarke to further support the firm’s capabilities working with entrepreneurial clients.